By Christine Dugas

Jim and Allison Wear don’t know a 5-iron from a wedge. But they recently moved with their two children into a new home in Cordillera, a residential community near Vail, Colo., that has three golf courses.

“It has a lot of non-golf amenities, like the spa and the national forest trail system,” says Jim, 42, a lawyer. “The setting is beautiful and we’re surrounded by open space.”

Although golf course living has long appealed to retirees and wealthy executives who can afford a second home in the Sun Belt, today younger families like the Wears are flocking to golf course developments. And to appeal to more home buyers, golf course developments are including nature trails, day care centers and fly-fishing clubs. This trend, like many other, is being fueled by the 78 million baby boomers born 1946 through 1964. From 1996 to 2011, a baby boomer will turn 50 every eight seconds, says Gerald Engle, CEO of Kensington Partners, which owns Cordillera, whose 6,500 acres include an equestrian center, children’s camp and spa.

And at 50, many boomers will have reached the point in their careers when they can afford a luxury home on or near a golf course.

In August, Len and Carol Sands moved into Harbor Pines Golf Club and Estates near Atlantic City, N.J. “I always wanted to live on a golf course. This house is right on the fairway,” says Len, 52, who owns two motorcycle dealerships.

In August, Len and Carol Sands moved into Harbor Pines Golf Club and Estates near Atlantic City, N.J. “I always wanted to live on a golf course. This house is right on the fairway,” says Len, 52, who owns two motorcycle dealerships.

There are more golf communities than ever to choose from. Since 1989, 793 have been started across the USA, according to Golf Research Group in Martinez, Calif. And those communities contain 456,000 home sites. Average home price: $366,500.

Exciting young pro golfers such as Tiger Woods have revitalized the sport and added to the allure. The National Golf Foundation says 24.7 million Americans played golf in 1996 vs. 19.9 million a decade earlier.

In that time, the number of African-American golfers nearly doubled, from 360,000 to 700,000. And women now account for about a third of the 2 million beginning golfers each year.

But in some golf course communities, only 30% or 40% of the residents play golf. “Golf is just a way to dress up real estate,” says Colin Hegarty, director of the Golf Research Group.

The attractions:

Security. About 42% of golf course communities are gated, Hegarty says. Even when they are not, they often have private security patrols.

“If the residents aren’t rich, they are affluent, and they take comfort in knowing that their home is protected when they travel,” says Richard Burke, president of Burke, Fox & Co., a golf community consulting firm in Savannah, Ga.

Cachet. “The quality of the golf course tends to elevate the image of the community,” says Gene Krekorian, a golf real estate specialist at Economics Research Associates in Los Angeles. “People are attracted to the image.”

Control. The communities usually have strict regulations on the number of homes and their design. “So you’re not going to wind up with a big surprise across the street,” Burke says.

Open space. Jeffrey and Marie Shepps were the first homeowners at Lake Las Vegas, a $4 billion golf resort built around a 320-acre man-made lake. Their home has views of golf course and the lake.

“One of the beauties of living here is that we’re surrounded by national park land,” says Jeffrey, 52, who owns an ad agency and several travel and tour companies.

But some golf communities are being built in metropolitan areas.

“It’s like living in the country here, but with access to the city,” says Ron Farrell, semi-retired head of a leveraged-buyout firm, who recently built a home in Country Club of the South, near Atlanta. Farrell, his wife, Marie, and their 10-year-old daughter, Alexandra, routinely go into Atlanta to attend professional basketball games and plays.

Golf courses with a touch of home

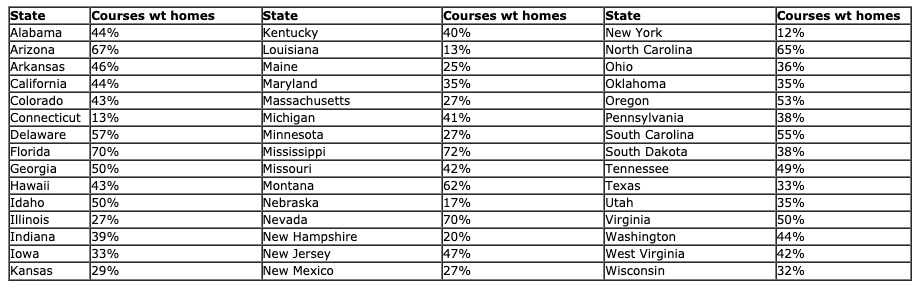

Nationally, 43% of golf courses include some homes or condos. Five states have no golf course developments, according to Golf Research Group:

Source: Golf Research Group, Martinez, Calif.

Environmental problems

Golf course developers have been criticized for bulldozing land and ruining the environment. In particular, many have come under fire for using valuable water to transform desert into lush landscapes. As a result, the developments can be subject to many environmental regulations.

“It took seven years to get all the approvals,” says Joseph Gurwicz, a partner in Max Gurwicz & Son, which developed Harbor Pines near Atlantic City. Gurwicz says 124 of the 500 acres are set aside for a nature preserve.

Today, developers talk about building golf courses to fit the terrain. To appeal to environmentally sensitive baby boomers, some are promoting conservation programs. Lake Las Vegas, for example, touts a wetlands park it is developing with the Audubon Society.

Another attraction: Although private golf clubs historically have excluded minorities, fair-housing laws require that golf course communities be open to people of all races and ethnic backgrounds.

“As incomes and job titles have moved up, a tremendous number of minorities have moved to golf communities , particularly those in south Florida,” says John David, executive director of the Minority Golf Association of America. “They want to be a member of a country club, but many are still closed to them.”

You only need money

The only requirement for entry to a golf community is the ability to afford a home, says Hank Thomas, president of the Jupiter Group, which is developing the Sports Acres golf course community in Miami. And the cost can be quite high.

Residents pay a premium for the lots – in some cases, nearly double similar lots in non-golf developments.

Even within a golf development, lot prices can vary considerably. At the Landings on Skidaway Island in Savannah, Ga., where Burke lives, a half-acre wooded , interior lot will cost about $40,000, while a half-acre on the golf course will cost $90,000 to $120,000, he says. The most expensive lot is a half-acre on the marsh, which will cost more than $200,000.

The homes are usually custom-built, within a set of guidelines. And they generally range from $200,000 to $10 million.

Then there are homeowner association fees, which go for such things as security and property maintenance. They can range from $250 to $1,000 a month, says Robert Dyson, president of Dyson & Dyson Real Estate, based in Rancho Santa Fe, Calif.

And that doesn’t include club dues. Dyson says a social membership can cost $500 to $1,000 for an initiation fee, plus $70 to $100 a month. A full golf membership, which usually includes unlimited use of the course, can run $7,500 to $100,000 for the initiation fee, with monthly dues in the $300 to $500 range.

“The upfront fees can be such a big hit that the club may finance them over a three- to five-year period,” Dyson says.

Despite the cost, luxury golf course property is in demand. A magazine dedicated to golf real estate is set to make a debut next year.

Mark Sullivan, editor of International Golf Course Estates, explains the attraction of golf communities this way: “They are like an adult playground, where everything is taken care of and the property is beautiful.”